Our ‘Plan-led’ planning system is under strain. Around 80% of the planning authorities in England are currently operating under the ‘presumption in favour of sustainable development’, either because their plan is out of date due to its age, or because of a lack of housing land supply, or historic under-delivery.

Planning reforms introduced over the last 18 months are bringing about concurrent local government reorganisation (through the amalgamation of district and county councils), local planning reform (through the re-introduction of strategic planning and a new tier of Spatial Development Frameworks), and Local Plan reform (through the introduction of a new 30-month local plan review process).

All this is happening at a time when the planning profession, and the public, are up-skilling on the use of AI and Large Language Models (LLMs) e.g. ChatGPT to prepare (dubious) planning statements and objections to planning applications.

Faced with the massive task of re-planning for the majority of England, how are planning officers supposed to address the deluge of AI slop that is going to be coming their way through the mandatory consultation processes involved in local plan making?

Table of Contents

Key Highlights Regulatory Context: The New Local Plan Process

Currently, the local plan making process takes an average of seven years from commencement to adoption. And this process must be repeated every five years to keep the plan ‘in date’. This is one of the issues that has led to the historically low levels of local plan coverage in England.

In late November 2025, the Ministry of Housing Communities and Local Government published guidance entitled 30-month local plan process: an overview that sets out the government’s expectations for preparing and adopting local plans within a 30-month timeframe.

Under this guidance, local planning authorities must structure plan preparation into defined stages, from initial readiness and publication of timetables through successive consultations, three mandatory gateway assessments, examination and adoption. Authorities are expected to use proportionate, meaningful engagement with stakeholders and communities. Early engagement on issues such as the plan vision, evidence base and proposed content prior to formal consultation is integral to achieving a sound plan within the statutory timetable.

The requirement to run a Scoping Consultation before the 30 month process is key to ensuring that the views of stakeholders, including the public, are included at the very start of the plan-making process. This should be done as part of the four-month notice period that Planning Authorities are required to provide to the Planning Inspectorate - all before the 30 month period officially kicks off.

Consultation is required again before the plan reaches ‘Gateway 2’. Local Authorities are required to publish the summary of their initial scoping consultation, then consult again on the proposed plan content, the evidence base that will be used to prepare the plan, and a summary of the plan, all in the first year. A third consultation, effectively on the final draft, will be required towards the end of the second year, before the plan making process reaches ‘Gateway 3’.

All this consultation will generate a lot of consultation responses from land promoters, planning agents, and the public.

Emerging Challenge: AI-Generated Planning Objections

Consultation on planning matters is one of the cornerstones of the democratic function of our planning system. It’s important to hear from the people that are affected by planning decisions.

But are we hearing from people any more?

Planning professionals, developers, and local authority officers alike are now highlighting a growing trend in which members of the public use generative AI to help prepare planning objections. Services (which we won’t name as it will only make the problem worse) generate objection letters and related materials for a fee, asserting that this helps individuals engage in the planning process. These tools can produce objections that cite policies and case law that they deem to be relevant to the application. The problem with this is that LLMs are infamous for overstating their confidence about what cases (or policies) are relevant - or even if they exist at all.

Experts have warned that widespread use of automated objection generation could strain local planning systems by increasing the volume of submissions that authorities must consider, some of which may include inaccurate or misleading references to policy and case law. Such developments risk shifting focus from substantive, place-based contributions to high volumes of text that do not materially aid decision-making. The prospect of “AI-powered NIMBYism” dominating the consultation record has been raised as a potential factor that could slow decision-making or undermine confidence in the integrity of public engagement.

While this issue hasn’t affected local plan consultations to the same extent as it has affected planning applications, yet. This is mainly because local plan making has been slow over the last few years; but this is set to change.

Why Traditional Consultation Routes Are Under Strain

Under the traditional approach to local plan consultation, authorities rely on a combination of statutory publications, stakeholder notifications, public events, and open submissions. These methods are effective where respondents engage as individuals or interest groups with genuine local knowledge.

The emergence of AI-assisted tools alters the operational landscape by enabling the rapid production of objection material that may lack grounded local insight. This can impose additional processing burdens on planning officers, who must review and respond to every valid representation in accordance with statutory obligations.

In an environment of resource constraints and pressing statutory deadlines, the increase in low-signal or templated responses can divert officer time away from core plan preparation and evidence synthesis functions.

The Case for Short-Form, Targeted, Evidence-Led Engagement

Given these pressures, short-form, demographically and geographically targeted engagement can offer valuable supplementary insight. Structured surveys provide quantified data on local attitudes in a format that is easier to analyse, report, and defend as part of an evidence base. Targeted surveying can ensure that feedback reflects defined segments of the local population and relevant neighbourhoods, supporting duty-to-involve obligations while reducing the likelihood of AI-generated bulk submissions affecting the quality of consultation records.

High-quality engagement data supports plan soundness by demonstrating how representative views have informed policies. It also enables authorities to identify priority issues and preferences at key decision points in the 30-month process, such as early scoping and evidence gathering, and during consultation on proposed plan content.

Give My View: A Practical Tool for Modern Plan Engagement

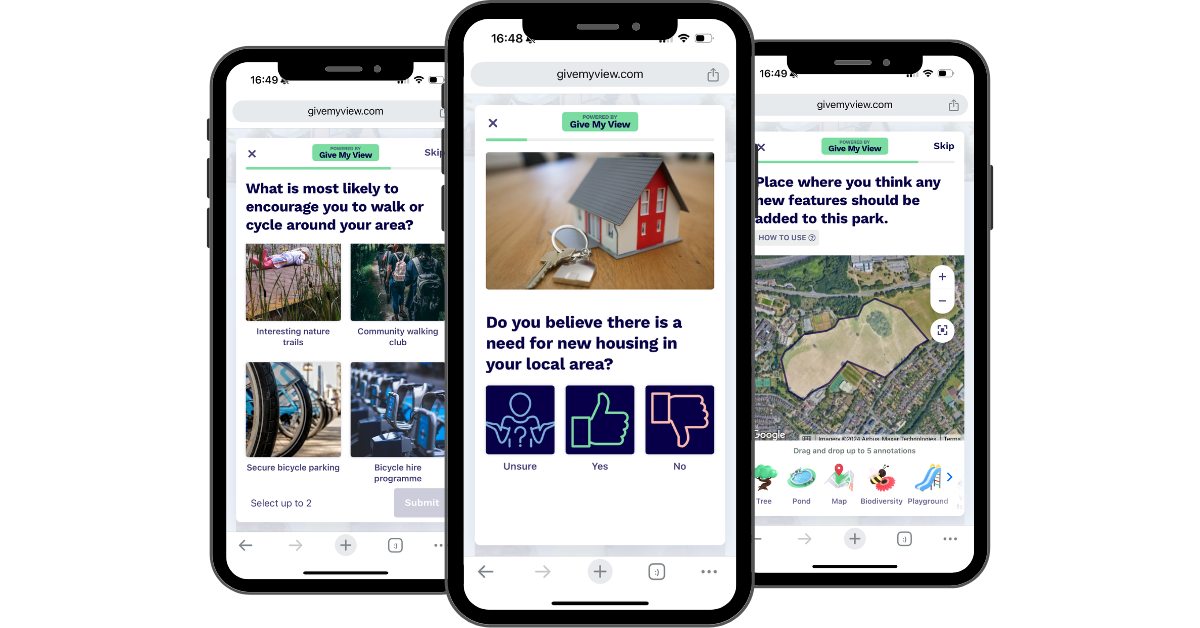

Give My View, a consultation platform developed by LandTech, is designed to assist local authorities and plan-making teams in obtaining structured, short-form public feedback that complements statutory consultations. By enabling authorities to deliver targeted surveys to defined demographic and geographic groups, the platform helps gather evidence that is both relevant and assessable. This approach reduces dependency on unstructured text-based submissions, and directly supports the requirements for proportionate and meaningful engagement set out in the new local plan guidance.

Give My View was recently shortlisted for the Royal Town Planning Institute’s Excellence in Digital Planning Practice award for its work with Flintshire County Council on planning documents. This recognition reflects the platform’s contribution to digitally enhancing public engagement and supporting evidence-led decision-making in plan preparation.

Implications for Local Authorities and Planning Consultants

Integrating targeted survey data into plan-making can help authorities demonstrate robust engagement and strengthen their position at inspection or examination. Consultants advising on local plan strategies can leverage such tools to provide clients with defensible evidence of community preferences and priorities, particularly where traditional consultation methods yield limited quantifiable insight.

By adopting digital-first consultation methods, authorities are better placed to manage the realities of the 30-month timetable while maintaining statutory standards for transparency and inclusivity. Evidence from structured surveys can complement qualitative submissions and provide a clearer picture of community sentiment that aligns with plan objectives.

Conclusion

The planning system is navigating simultaneous pressures: statutory reforms that demand accelerated plan-making and the proliferation of digital technologies that affect consultation dynamics. The new 30-month local plan process establishes clear expectations for authorities to engage early and proportionately with communities.

At the same time, the rise of AI-generated objection tools underscores the need for high-quality, structured engagement mechanisms that produce representative evidence of local views.

Platforms such as Give My View offer practical support for these goals by facilitating targeted, evidence-based public feedback that enhances the integrity and efficiency of plan preparation in a rapidly evolving digital environment.

Book a demo of Give My View to see how targeted, evidence led surveys can strengthen your local plan engagement and stand up to inspection.